- Home

- Startup news

- Found: the missing piece to create natural red colors

Found: the missing piece to create natural red colors

Lantana Bio is revolutionizing the natural color market by using baker’s yeast to produce anthocyanins more sustainably. This innovative approach offers a scalable, eco-friendly solution for cosmetics and food industries, meeting rising consumer demand for natural ingredients.

Flavonoids and anthocyanins are a group of plant compounds with numerous health benefits. They are also responsible for the red, purple, and blue colors found in flowers, fruits and berries. These aromatic compounds are traditionally extracted from plants for use as functional ingredients and dietary supplements, or as natural colorants for foods, beverages, or personal care products.

The problem with extraction, though, is that it is very resource-intensive. It requires substantial amounts of land, water, and agrochemicals to obtain a relatively low yield, explains Michael Naesby, co-founder of Lantana Bio. “The concentration of anthocyanins in plants is very low, typically measured in milligrams per kilogram.”

Producing the molecules outside of plants wasn’t possible—until recently. “The anthocyanin pathway in microorganisms has always been tricky because a key enzyme from the plant process was missing,” explains Naesby, who had been working for years for small biotech companies, including on building plant pathways in yeast. After his last role ended, he kept in touch with former colleagues and got some ideas on paper on how to improve the anthocyanin pathway in yeast.

“We found the missing piece to complete the pathway. We filed a patent, started a company, and had proof of concept that we can in fact make anthocyanins in microorganisms—probably as the only group in the world,” says Naesby. “But this was all mostly on the drawing board. We needed lab space if we wanted this idea to grow.”

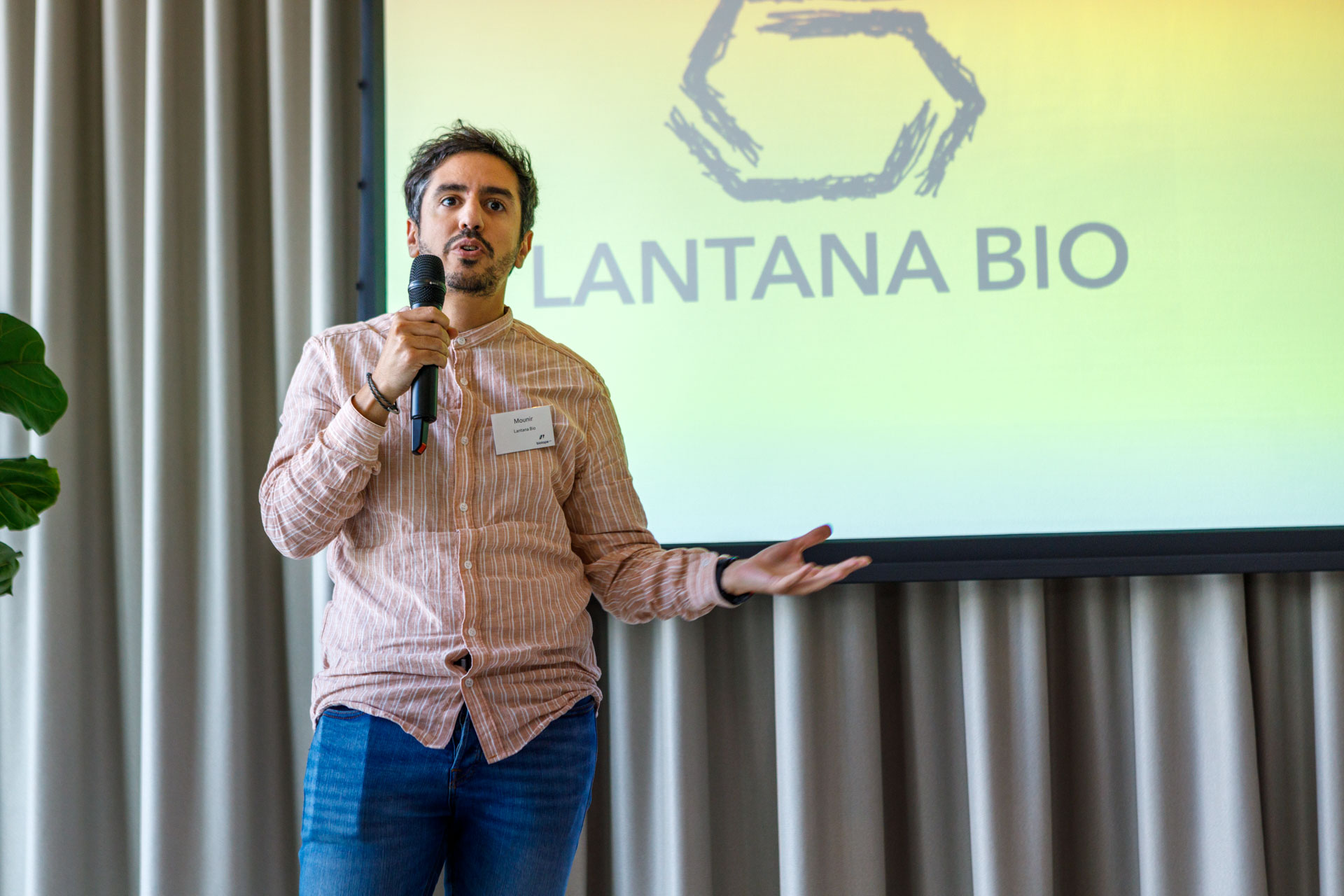

Naesby got in touch with Mounir Benkoulouche, another former colleague, based in Toulouse. Benkoulouche, a longtime advocate of industrial biotech and entrepreneurship, was immediately interested in diving into the natural color space.

Benkoulouche: “I have always wanted to apply my expertise in a meaningful way and contribute to a more bio-based economy. Finding a more sustainable way to produce colorants will definitely make an impact.”

Together with three other co-founders—IP and legal expert Morten Birkeland, polyphenol metabolism expert Stefan Martens, and yeast engineering expert Michael Eichenberger— Naesby and Benkoulouche officially launched Lantana Bio. The company’s name was inspired by the Lantana flower, known for its vibrant flowers that come in yellow, orange, red, and purple hues—representing the diverse natural colors Lantana Bio aims to create using biotechnology.

Brewing colors, much like beer

What makes Lantana Bio’s approach unique is that the anthocyanins they produce are identical to those found in plants, allowing them to be sold as natural molecules. This is a major advantage in a multi-billion-dollar market that is increasingly focused on sustainable, bio-based solutions.

“There are other natural colors on the market, but most are extracted from plants,” explains Naesby. “One other significant group of natural pigments are betalains, derived from sources like red beets. These have been commercially available for around 5 to 10 years after their biosynthetic pathway was fully understood.”

Anthocyanins, however, which Lantana Bio focuses on, are one of the largest groups of natural colorants, alongside carotenoids. Each color group has distinct properties, such as solubility in water or fat and stability, making them suitable for different applications.

“We’re addressing a huge market gap by creating anthocyanins using fermentation,” says Benkoulouche. Similar to brewing beer, their technology enables yeast cultures to produce anthocyanins at levels that are 100-1000 times more concentrated than those found in plants. This process is not only more economically viable but also significantly more sustainable.

“Yeast has been used for centuries in fermentation, making beer, wine, and bread,” says Naesby. The yeast strain Lantana Bio uses is Saccharomyces cerevisiae, commonly known as baker’s yeast, but since Lantana’s purification method ensures that no trace of yeast remains in the final product, the anthocyanins is considered a natural ingredient.

Refining the positioning

For Lantana Bio, the biotope basecamp experience has been an invaluable learning journey, especially in areas where the founders are not specialists. “We’re experts in science and biotech, but there’s so much more to running a startup—business strategy, regulatory aspects, fundraising, and partnering with corporates,” says Benkoulouche. “These are the things you can’t just learn by reading online. The openness of people in the biotope ecosystem to share their knowledge made a huge difference.”

The workshops also helped the co-founders to structure their ideas. “We knew the concepts, but sitting down and putting words to them, creating a cohesive branding for the company, was a great exercise. It really helped us focus on what we need to do: sell products.”

The initial focus of Lantana Bio is on the cosmetics and food industries, particularly in France, where the demand for natural colors is high. “Being in France, with its many large cosmetic companies, makes it an ideal market for us,” Benkoulouche adds. In food industries as well, demand for sustainable, bio-based products is rapidly growing.

Their yeast-based process, which is GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe), is efficient and scalable, making Lantana Bio well-positioned to disrupt the natural color space with sustainable innovation, by offering a cleaner, more efficient way to produce anthocyanins.

“Regulatory approval is a long and costly process, but we know it can be done. We’ve seen other molecules produced by precision fermentation in yeast successfully go through.”

Mounir Benkoulouche

Next steps

Naesby, Benkoulouche and the rest of the team of founders are now preparing for their next big milestone: securing a seed round to help scale up production and move towards commercialization. “Our goal within the next 12 to 18 months is to secure seed funding, onboard more R&D staff, and start the regulatory process for selling precommercial samples,” says Benkoulouche. For now, the company remains focused on both the cosmetics and food industries, with regulatory approval in cosmetics expected to come through the REACH regulations in Europe.

“Regulatory approval is a long and costly process, but we know it can be done. We’ve seen other molecules produced by precision fermentation in yeast successfully go through,” he explains. While Europe is the initial focus, the US market is also a priority because of its size and faster regulatory timelines.

To achieve these goals, Lantana Bio is looking for partners in both production and distribution. “We’re tapping into biotope’s network to find partners who can help scale up production and distribute our products to the right markets,” says Naesby. The team is also well-connected in the Toulouse region, where they’ve built a strong local reputation. “It takes time, but by consistently engaging with people in the ecosystem, we’ve been able to build our name in the biotech space.”

But Lantana Bio has ties across Europe, including connections to the Belgian and Flemish biotech ecosystems. “We were already connected with UGhent through a Horizon program, and we see a lot of potential for further cross-border collaboration,” Naesby shares. With a growing reputation and a strong network of partners, Lantana Bio is positioning itself as a key player in the global natural color space.

More News

The fundraising mirage

Typcal is brewing the future of pragmatic protein

AmphiStar secures €12.5m EIC funding

biotope recap: Summer edition

Annick Verween on the VCo2 podcast

2024 wrapped

Networking with cohort six

B’ZEOS celebrates seed round milestone

Tackling food waste at its source

The value of good mentors

Meet our Spring ‘24 cohort

His son’s allergy turned this father into a founder

FlyBlast: on a mission to solve meat

Biosurfactants from food waste? Meet AmphiStar

Probitat interview

B’ZEOS: sustainable packaging made of seaweed

Elogium: Poultry probiotics for safer food

Launch of Biotope ventures fund

Bolder Foods: non-dairy cheese for a better world

BioVox article

Have you got what it takes?

- Pressure-test your biotech with expert feedback

- Align your team and sharpen your strategy

- Turn your startup into an investment-ready business